The paradigmatic story of the deal with the devil evolved culturally and artistically alongside society’s struggles. How is humanity to cope with ambition and the fear of death?

Abigail Leali for Mutual Art

Not marching now in fields of Thrasymene,

Where Mars did mate the Carthaginians; …

Nor in the pomp of proud audacious deeds,

Intends our Muse to vaunt her heavenly verse:

Only this, gentlemen,– we must perform

The form of Faustus’ fortunes, good or bad: ….

So soon he profits in divinity,

The fruitful plot of scholarism grac’d,

That shortly he was grac’d with doctor’s name,

Excelling all whose sweet delight disputes

In heavenly matters of theology;

Till swoln with cunning, of a self-conceit,

His waxen wings did mount above his reach,

And, melting, heavens conspir’d his overthrow;

For, falling to a devilish exercise,

And glutted now with learning’s golden gifts,

He surfeits upon cursed necromancy …

From this first epic invocation in Christopher Marlowe’s 1604 play, Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, the audience is faced with a perplexing arrangement. Doctor Faustus, a man purported to possess a prodigious capacity for theological studies, has fallen afoul of what ought to be one of the simplest of Christian teachings: Do not summon the devil.

Faustus has been gifted with a genius intellect and ample opportunity to achieve worldly success. Like Icarus of the “waxen wings” (or like Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden), to remain in safety Faustus need only abstain from seeking danger. But in the end, of course, he cannot resist. Desiring knowledge and power vastly in excess of what his humanity can support, he refuses to accept any of the signs calling him to repent, and he is dragged to hell. Why, Marlowe begs us to wonder, did Faustus desire greater knowledge? And why was this desire a problem at all?

The artists of the Renaissance were especially attuned to the possibility of having “too much” of any one quality – in fact, it was rather in vogue. There is a certain depression-like disposition referred to as “Renaissance melancholy,” in which a man succumbs so fully to his sadness that it exhibits itself as excessive emotion of all kinds: laughter, crying, outbursts of rage.

Albrecht Dürer, Melancholia I, 1514

While these melancholics may not have been happy per se, they were generally seen as geniuses in math, science, writing, and the arts. In Albrecht Dürer’s famous Melancholia I, an extremely pensive and frustrated figure sits on a bench, surrounded by evidence of his technical mastery of all kinds of crafts. His frustration represents the dark side of the typical “Renaissance man.” Just as today would-be business gurus and the nouveau riche go above and beyond to give off the impression of intelligence or wealth, so aspiring Renaissance men in Marlowe and Dürer’s day would conflate melancholy with intelligence, striving to become as miserable as possible – without actually going insane.

In this context, Faustus’s desperation to achieve excellence in academics, even at the cost of his soul, becomes all the more poignant. Underlying a deceptively complex discussion about the nature of free will is a more subtle warning against the prevailing humanist assumptions in his own day: At what point, he seems to ask, might the race to ever-higher heights of human achievement cut our humanity out of the picture entirely?

A couple hundred years later, the Faust narrative would be revitalized in Goethe’s two-part play, Faust. A more philosophically complex rendition, the play nevertheless addressed the Victorians’ new way of approaching this humanist dilemma at the height of the Industrial Revolution.

Anton Kaulbach, Faust und Mephisto, late 19th – early 20th c.

In this new approach to the story, Faust is no longer merely an individual agent; his overweening desire for pleasure and excellence pose a genuine threat to others as well. This thematic shift reflects the increasing interconnectivity of the post-industrial world, in which business magnates’ insatiable greed could no longer be ignored as an isolated act of selfishness. Their sins and failings were quickly gaining the power to make or break entire nations.

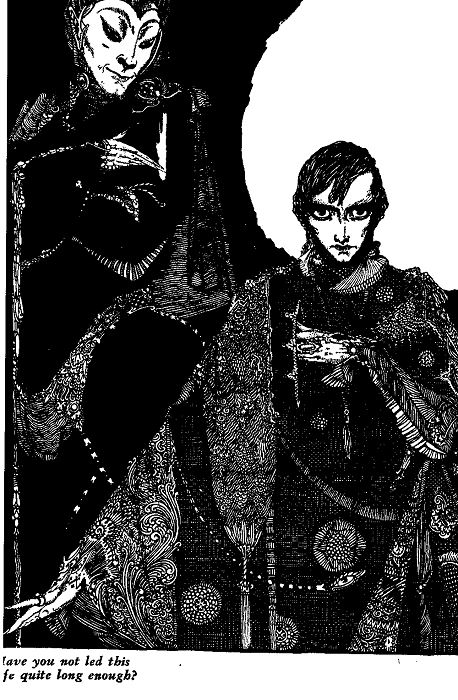

Harry Clarke, Illustration for Goethe’s Faust, 1925

In 1925, Harry Clarke would create another Faust illustration in a style reminiscent of the work of decadent artists like Aubrey Beardsley. In Clarke’s depiction, Faust is a younger man, dressed in the opulent clothes of royalty. He is pictured with an air of solemn confidence, staring directly, unflinchingly at the viewer – albeit overshadowed by the cruel grin of the demon Mephistopheles, who towers behind him, unseen. As the Industrial Revolution gave way to the First World War, which in turn paved the way for the Second, Clarke’s piece demonstrates how the increasing political and technological prowess of humanity was allowing younger, more ambitious and cunning men to mold in their hands the fate of the entire world.

It might be easy, at first glance, to see the Faust story as a relic from a Puritanical time, in which black-and-white morality tales were used to form the ethical sensibilities of a largely uneducated populace. But that would not be fair. Rather, the ongoing narrative trajectory of Faust’s story serves to express the deep fear undergirding a society that is ever more glutted on advancement and achievement: In the end, we might all find out that it is possible to have too much of a good thing.

Ultimately, one need simply look at our own modern struggles with complex issues like a shifting work culture, social media addictions, artificial intelligence, and globalized trade networks not only to empathize but also to resonate with this historical concern. No matter how noble the aims, no matter how positive the possible outcome, the core proposition of the story is that the ends can never justify the means. A solution that fails to take into account the limitations – and the dignity – of the human being will never be a solution at all. It will only be the hubris of Icarus, melting his wings in his effort to get closer to the sun.

Arnold Böcklin, Self-portrait with Death playing the fiddle, 1872

It is here that I would like to turn briefly to Arnold Böcklin’s Self-Portrait with Death Playing the Fiddle. While not strictly a “Faust” painting, its composition and themes bear obvious similarities to paintings like Faust und Mephisto. In it, the skeletal figure of death plays his lonely note, and Böcklin pauses, his brush in midair, to listen over his shoulder. But something is different here. The temptation and the threat are no longer grotesque or laughable but morbidly compelling. For Böcklin, the reminder of death serves a dual purpose: it inspires his art, even as it drives him towards despair of its worth. This is not the result of Renaissance melancholy, at least in an affected way. Rather, it is the fruit of real melancholy: the harrowing recognition of one’s own death.

Memento mori, goes the ancient phrase. Remember you will die. In his quest for domination – of himself, of others, of the world, of God – Faust’s greatest failure was to forget that he himself was mortal. No matter how powerful he may have been in a given moment, the very next moment he could be dust.

Not only does Böcklin’s painting diagnose this failing but it also provides at least a sliver of a way forward. In attuning himself to the song of that morbid fiddle, he suggests that the way to achieve greatness may not be to do battle with our limitations at all. It is not to give into hubristic desires and seek to become a god. Rather, it is to embrace one’s life as it is, to recognize that all the power or pleasure in the world would mean nothing without death, and at last to turn it into something beautiful.